The One Vision One Voice program (OVOV), in collaboration with the University of Toronto’s Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work (FIFSW), has released a research report that looks at child welfare investigations of Black families in Ontario and how they compare to investigations involving white families. The report, Understanding the Over-Representation of Black Children in Ontario Child Welfare Services, uses data from the 2018 Ontario Incidence Study to evaluate the extent to which race plays a part in child protection work in Ontario.

Keishia Facey, manager for OVOV, explains how these findings can support better outcomes for Black children, youth, and families in Ontario.

What does the report tell us about the experiences of Black children, youth, and families in the Ontario child welfare system?

The report shows us how anti-Black racism is leading Black children, youth, and families to the child welfare system. It allows us to see how child welfare intersects with other systems, and how racism within the various systems is leading to the disparate and disproportionate outcomes for Black families.

What are the key findings/takeaways of the report?

One of the key findings is around referrals. Investigations involving Black children are almost twice as likely to be initiated by schools versus those involving white children. Clearly, we have a lot of work to do to interrupt that pattern.

More generally, the findings show that child welfare is just one part of a multi-faceted structure with many systems that intersect. We have to interrogate at a deeper level all of the various policies and practices across systems that lead to disparities and disproportionalities for Black families. And the work needs to happen at all levels simultaneously. We can’t just be focused on improving outcomes in child welfare. We have to do that at the same time that we’re talking to government about accountability, and referral partners about changing their practices, and so on.

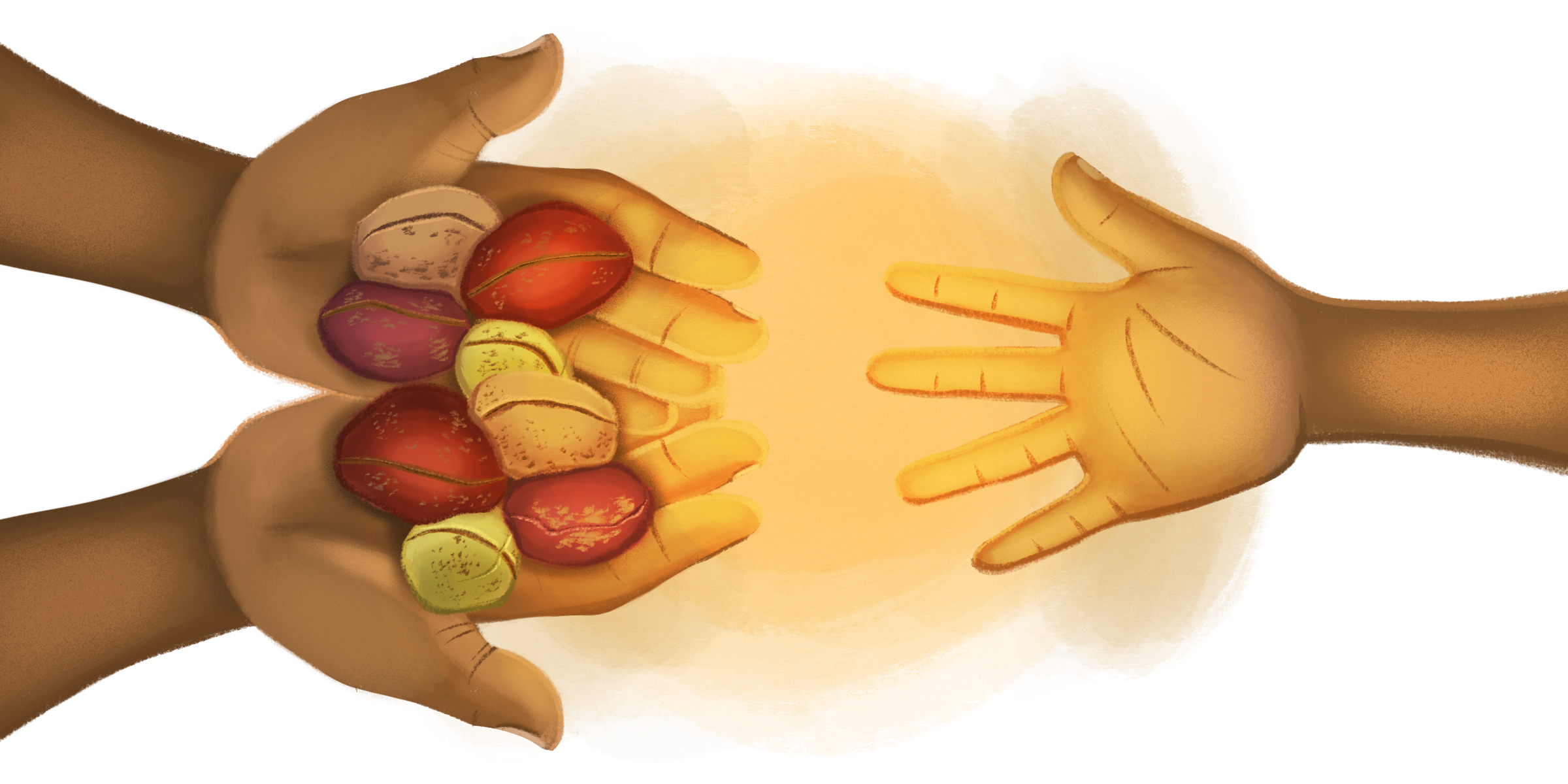

What is the significance of the report’s cover art?

We worked with a talented Black illustrator, Chelsea Charles, on this report. We decided to use the kola nut to honour West African culture and the African diaspora. The kola nut is often used as a symbol of unity and welcoming in ceremonies. But it’s actually really bitter. So, that is also playing a symbol, in that the data in this report is hard to read, a bitter pill to swallow in a sense.

Illustration by Chelsea Charles

chelseacharlesillustration.com

Was there one data point that surprised you?

The data aren’t surprising. The Black community has been telling us this for so long.

But the findings around socioeconomic factors stood out. But not in the way you might think. I’ve done a lot of direct service work with people living through poverty and other social determinants of health, so seeing it laid like this really hit home. It’s not that Black families are poorer, so they have more trouble caring for their children. It’s that they are surveilled and policed more and therefore come into contact with systems more. The data point around housing is evidence of this. Because we know oversurveillance takes place in public housing. And then that oversurveillance feeds into schools and police involvement, where there is bias and racism, leading to calls to child welfare instead of more appropriate linkages to community-based referrals.

Why is this report important?

The report is an important tool for advocacy. Data are powerful storytellers, so it’s another way we can create change within child welfare, but also with government, referral partners, and other intersecting systems.

Despite talking more openly about the disparities and disproportionalities for Black families in child welfare over the past 7 years, overrepresentation still exists. It’s not being fully addressed despite all the interventions being put into place. This report shows us that we need to do something bolder to see those changes. There is a lot of good work happening in the sector. And that’s great. But more is needed.

Mashkiwenmi-daa Noojimowin: Let’s Have Strong Minds for the Healing

In 2021, a similar study was released examining the incidence of investigations for First Nations children, youth, and families was released. Read more about that research and download the report here.

What do you want those working with Black children, youth, and families to know coming out of this report?

Knowledge is power. So, we hope that all frontline staff read this report and see their role in the work—see how they can create partnerships, engage with Black-led organizations, look at their work through an anti-Black racism lens, and ultimately improve the lives of Black children and youth. Their role is critical.

And yet, we know that they are bound by policies and procedures that lead to decisions that aren’t necessarily in the best interest of Black families. We have to focus on that as well.

How is the report connected to OVOV’s other priorities?

Since OVOV’s inception, there’s been a big push to get race-based data. And now that we have it, we can harness it to better understand what exactly is leading to the disparities so we can work to address those inflection points. Our Disparity Mapping Project with FIFSW’s Youth Wellness Lab is the next step in understanding the points along the child welfare service continuum where Black families are experiencing these disparate outcomes.

We also have an African Canadian service best practices guide coming out in September that will provide child welfare agencies with key considerations for how they work with Black families. And our Navigating Child Welfare resource directly addresses the idea that Black families need specific support navigating Ontario systems because they are not designed for them.

Then we have leadership development initiatives where we’re looking at who is making the decisions within child welfare. Because that ultimately impacts the services families receive.

Everything is connected. I see the report as the what and everything we do is the how. As a team, we’re committed to using this data to inform our work and ultimately, support our members to improve outcomes for Black families in Ontario. Because that’s what it’s all about.

Click here to read the full report. To learn more about the One Vision One Voice program, visit www.oacas.org/onevisiononevoice.