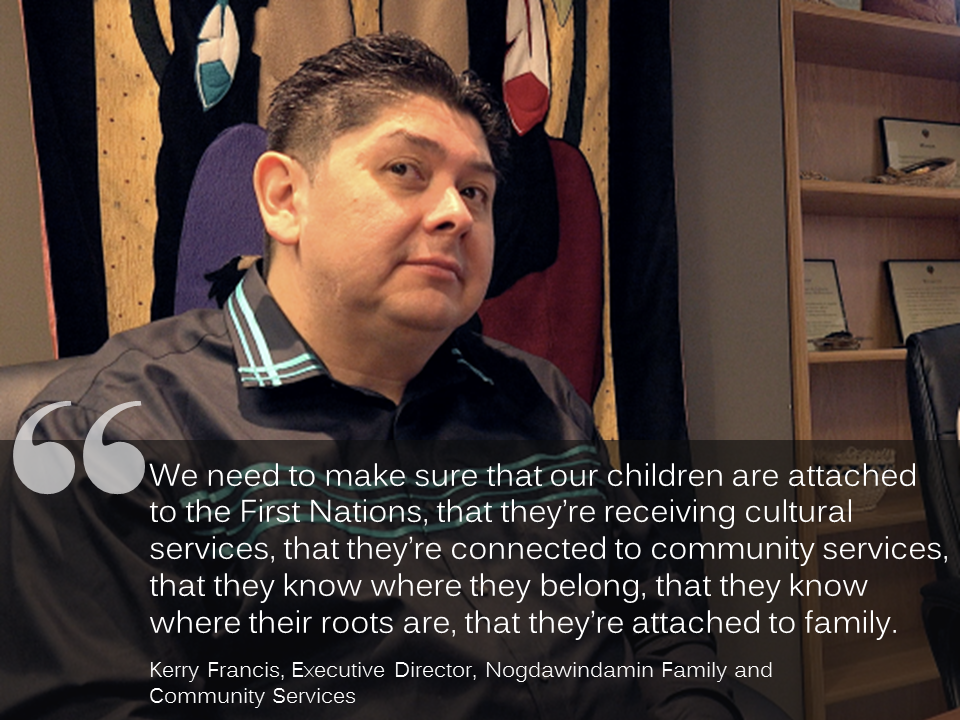

Kerry Francis, Executive Director of Nogdawindamin Family and Community Services, sat down with us recently to talk about his organization’s designation, the journey it took to get here, and what it means to him and to the First Nations communities of the North Shore.

On April 1st, 2017, Nogdawindamin Family and Community Services (NOG) assumed responsibility as the recognized child welfare authority for Lake Huron North Shore First Nations. Congratulations! Can you tell us first what it means to be a designated agency, and the process it took your organization to get here?

What does it mean? Wow. What a celebration. I’m truly honoured in my capacity as Executive Director to have been part of this journey for the past seven years. Nogdawindamin has been around for almost 27 years, but these last seven have truly been the most intensive in terms of building our capacity to accept responsibility for child welfare in the seven North Shore First Nations. So I guess that’s how I’d like to answer that question. It’s just so powerful. I’m not sure that it’s even settled with me yet.

And how would you define what it is to be a designated child welfare agency?

Designation means that we’ve received approval [from the Ministry of Children, Community and Social Servicess (MCCSS)] to provide child welfare services under provincial legislation. But for us it’s also about providing those services in a culturally relevant way.

What were some of the biggest challenges you faced getting designated?

Understandably and respectfully, we had to go through the whole MCCSS capacity framework, their guidelines, and their stages. It probably took us the equivalent of six years to get through that extensive process. But let me tell you, there was an incredible amount of collaboration with the Ministry throughout.

But there was also a tremendous amount of work to be done to build partnerships with the seven First Nations in our jurisdiction. Certainly, it’s not an independent thing we’ve done. This has been a true partnership between our agency and the First Nations.

Why is designation significant for Nogdawindamin and the First Nations communities and families you serve?

Well, it’s significant from a First Nation and parent’s rights perspective. These communities never gave up their inherent right to the children we have assumed responsibility for. In the past year I’ve heard so many chiefs talk about how we need to reclaim jurisdiction of our kids. We need to make sure that our children are attached to the First Nations, that they’re receiving cultural services, that they’re connected to community services, that they know where they belong, that they know where their roots are, that they’re attached to family.

The designation of NOG requires that the Children’s Aid Societies of Algoma and Sudbury give up authority for child welfare services in your communities. This restoration of jurisdiction is a priority of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and also for child welfare in Ontario. How did NOG work with these agencies through the designation process?

I have to say that the two societies were very supportive. We did have some challenges, but we were always able to come to the table, have a coffee, have a conversation, and address what those challenges were. They were very supportive in terms of information sharing, accessibility, providing mentorship, and secondment support to our staff to make sure that they understood the role of child welfare, standards, legislation, and legal processes.

And how will NOG continue to work with these neighbouring societies going forward?

There’s a lot of mutual respect between Nogdawindamin and Sudbury, and Nogdawindamin and Algoma. We now have two completed inter-agency protocols which outline how we’re going to work together. Because we are dealing with two large urban centres, Sault Ste. Marie and Sudbury, our work together will continue.

How would you differentiate the services that your agency will be providing versus those that the Children’s Aid Societies were providing?

Well obviously we’re required to meet the CYFSA and all the standards that come with child welfare in Ontario. But we are providing a different service.

When we started the whole capacity development process, I was told by the board, the previous Executive Director, and the chiefs to make sure that we had conversations. So we did. We went out and had conversations with chiefs, council members, elders, some folks that were involved in child welfare, and some that were not.

Through such a comprehensive process we ended up with close to 72 recommendations. And I can tell you that we’ve looked at all those recommendations in the past seven years to ensure they have been built into our process.

One of the largest areas we were asked to consider was to bring back the culture: bring back ceremonies; bring back teachings; bring back talking circles. Up until about three years ago NOG was operating with one elder in residence. Today we are operating with four elders in residence, who are working with kids in care, our alternative care parents, and our staff. They’re also helping to mediate and facilitate talking circles.

Can you give some other examples of how you have built culture into your process?

One of the beautiful things we’ve done is place our child welfare teams right in the First Nations. This allows for the holistic and wraparound process of our child welfare model, with staff sitting at the table with prevention staff, band reps, other community health and social service providers and facilitating case reviews with families – creating plans so that families and kids are receiving the services they need. So that’s what our model is all about, and of course, including elders and the culture in that whole service planning methodology.

Customary care is another component we’ve built into our child welfare practice. We’ve inherited a total of 52 court files from Algoma and Sudbury. What our leadership and our board have instructed us to do is to look at alternatives. Can these cases be managed through customary care agreements involving the First Nation band reps and the community-based prevention team?

Can you explain customary care and how it’s different from other forms of care?

Our interpretation of customary care involves Mom, involves Dad, and involves the First Nation. Collectively we’re placing kids outside their homes. Placing kids is not what we want to do. If we can keep kids at home, that’s what we’d like to do. But in circumstances [where kids need to be placed], it’s a collective decision: either placements with aunts, uncles, grandmothers, grandfathers, or other members of the community. Our focus is placing kids within Indigenous or Anishinabek families.

When we started our transition process we had 12 kids placed under customary care. Through transition we’ve now reached over 42 kids. And we are opening customary care homes. Right now we’re operating 71 approved homes. So we have a large resource in terms of accessibility for placement.

That’s incredible. We’ve heard that finding approved customary care homes is a challenge for designated agencies. It sounds like this is a real area of strength for NOG.

It is. But I have to tell you, about 14 months ago, our agency was operating with less than 35 homes. So we made a huge investment. We established a recruitment team, with a supervisor and three staff. And they were able to push our numbers beyond 71 homes. Right now we can accommodate 100 children with those resources.

What are some of the challenges faced by the families that Nogdawindamin works with?

From a community perspective, one of the biggest challenges we’re facing right now is accessibility around children’s mental health. I sat in case reviews yesterday and the majority were requests from parents to place teenagers because of behaviours. These are kids who are unable to cope and have no access to children’s mental health services.

To clarify, these kids are intersecting with child welfare because their families are challenged by their behaviour, and child welfare is one of the few places there might be support?

Yes.

So it’s not necessarily about families being investigated for issues of maltreatment. It’s more the general lack of resources in the area?

That’s right.

Our board has taken a strong position with the support of the seven First Nations that we want to provide our own cultural children’s mental health model under Nogdawindamin. And the province has said recently they’re prepared to sit with us to look at a model.

What makes this work so meaningful to you?

Our agency has its own drum. And what really hits me hard is when I hear that drum. I’m even getting emotional now. For me and my Director of Service, Karen Kennedy, when we hear that drum it just reminds us of why we’re doing this. And it’s about meeting the needs of those 120 kids in care.

In addition to that, it’s also about assisting the First Nations to meet the needs of the kids involved with child welfare, and providing support to Moms and Dads to be able to achieve a healthy life and to meet their milestones. That’s what really hits us hard.

How will your agency be celebrating its designation?

We are going to have a huge celebration. It’s going to be in one of our central communities, hosted by Chief Elaine Johnston and her leadership. We will be opening our day from a cultural perspective with a sunrise ceremony at 6:45 a.m., followed with an official cultural grand entry involving some of our kids dancing in their jingle dresses.

One of the things we’re trying to do is complete a welcoming home ceremony for some of the kids that we’ve accepted responsibility for, to acknowledge those kids, and to accept the ownership on behalf of the First Nations.

It will certainly be a milestone achievement day for these seven First Nations and Nogdawindamin.

First Nations in the North Shore

Atikameksheng First Nation: Atikameksheng Anishnawbek are descendents of the Ojibway, Algonquin and Odawa Nations. The First Nation is located approximately 19 km west of the Greater City of Sudbury. The current land base is 43,747 acres, much of it being deciduous and coniferous forests, surrounded by eight lakes, with eighteen lakes within its boundaries. The total population is about 1220 members.

Sagamok Anishinawbek: Sagamok Anishinawbek, whose name means ‘two parts joining’ is a located approximately 120 kilometres west of Sudbury. Sagamok’s culture and language is Anishinabek and is made up of the Ojibwe, Odawa and Pottawatomi tribes. Also known as the Three Fires Peoples, the community members of Sagamok number well over 2000. A little over 50% of the membership lives on reserve, with the remainder living in urban locations.

Serpent River First Nation: The Serpent River First Nation is part of the unceded lands retained by the Ojibway who traditionally inhabited the North Shores of the St. Mary’s River and the Georgian Bay. The Serpent River First Nation is located approximately 160 kilometers east of Sault Ste. Marie, or approximately 140 kilometers west of Sudbury. The reserve consists of a land base of 26,947 acres along the north shore of Georgian Bay. The residents are of the Ojibway Nation, totally approximately 1,381 members.

Mississauga First Nation: The community is located at the mouth of the river which shares its name, The Mississaugi. Spoken in the anishnaabemowin language it is Misswezhaging, which means “many outlets”. Although the community is located within the “reserve” boundary, the Traditional Territory extends towards the Huron Watershed. Mississauga ancestors and current Mississauga’s travel the extent of the Mississaugi River utilizing its abundant resources. Today the First Nation has a population of approximately 1,120.

Thessalon First Nation: Thessalon First Nation is 4 square miles that consist of residential and commercial space. Thessalon First Nation consists of the lake shore settlement of 2,261 acres as well as the 104 square miles North of Thessalon Township. Today Thessalon First Nation has a population of nearly 732 Band Members.

Garden River First Nation: Also known as Ketegaunseebee (Gitigaan-ziibi Anishinaabe in the Ojibwe language), Garden First Nation is an Ojibwa band located at Garden River 14 near Sault Ste. Marie. Garden River First Nation has a population of 2,134 members. The Garden River reserve consists of two non-contiguous areas, totaling 51,159 acres.

Batchewana First Nation: Batchewana First Nation is an Ojibway First Nation whose traditional lands run along the eastern shore of Lake Superior, from Batchawana Bay to Whitefish Island. The First Nation has a total population of 2,400.