Residential Treatment Outcomes with Maltreated Children Who Experience Serious Mental Health Disorders

By Shannon L. Stewart, Child and Parent Resource Institute; Alan Leschied, The Faculty of Education; Courtney Newnham; Lyndsay Somerville; Al Armieri; The Faculty of Health Sciences; The University of Western Ontario; Jeff St. Pierre; Child and Parent Resource Institute, London Ontario

ABSTRACT

This study explored long-term outcomes for children with histories of maltreatment who were referred directly from a community’s child protection service to an intensive residential mental health treatment program. The results for children referred from child protection showed that their reduced symptom trajectories reflected favourably when compared to children with mental health symptoms of a similar nature and degree who were not under Crown wardship at the time of admission. Reductions within the maltreated group reflected a decrease of approximately 40 percent, relative to symptom levels at admission, two years following their admission. Residential treatment within the children’s mental health system is often referred to as the “last chance” for children and youth with serious mental health disorders. It is encouraging, therefore, that intensive residentially based service for the study group can have a positive effect on mental health symptoms. However, the long-term outcomes from treatment are dependent on the nature and quality of the follow-up services at discharge. If this intensive and expensive form of service is to have a maximum effect, close co-ordination between residential and community-based treatment providers is a necessity.

INTRODUCTION

Poor long-term treatment outcomes for children/youth with histories of physical abuse, sexual abuse and/or neglect reflect the challenge of providing effective interventions with this population (Conner, Miller, Cunningham & Melloni, 2002). While there is some research identifying significant positive gains from intensive short-term residential treatment for seriously mental health disordered (SMHD) children/youth without maltreatment histories (St. Pierre, Leschied, Stewart & Cullion, 2008; Green et al., 2007; Lyons, Martinovich, Peterson, & Bouska, 2001), these results have yet to be replicated with a child welfare sample. The primary objective of this study was to examine the differential impact of child welfare status in predicting treatment gains and sustainability for up to two years following discharge from residential treatment.

LITERATURE REVIEW

There are numerous explanations for why children who experience maltreatment are more resistant to therapeutic change. The one most often cited reflects the very nature of the abuse itself, suggesting that childhood victimization is related to numerous chronic mental health outcomes including post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression, self-abuse and suicide (Allen, 2008; Fergusson, Boden & Horwood, 2008). The subsequent involvement in the child protection system itself has also been linked to poor outcomes. Repeated placement failures for maltreated children once admitted to child welfare care perpetuates an inability to form trusting relationships, thereby compromising the formation of a therapeutic relationship (Cloitre, Koenen, Cohen, & Han, 2002; Hughes, 2004; Saywitz, Mannarino, Berliner, & Cohen, 2000; Leslie et al., 2005; Hughes, 2004; Saunders, Berliner, & Hanson, 2004; Newton, Litrownik, & Landsverk, 2000).

RESIDENTIAL TREATMENT

Residential treatment (RT) within the spectrum of the children’s mental health system serves as a tertiary care provider, reserved for children with serious mental health disorders (SMHD). However, the outcome literature related to RT in children’s mental health has only recently been developed, since RT has been identified as the most expensive form of service due to its intensity and access to a full range of treatment professionals (Bates, English, & Kouidou-Giles, 1997). Frensch and Cameron (2002) suggest that RT is a “last chance” intervention for children with SMHD. Two studies by Lyons and his colleagues (1998; 2001) suggest that it can be a promising approach. Green et al. (2007) report encouraging results related to RT. St. Pierre et al. (2008), in a two-year follow-up related to RT, indicate that reductions in mental health symptoms can be identified two years after treatment discharge, averaging a 40 percent reduction in externalizing disorders. However, no studies to date have focused on the impact of RT as it relates to achieving reductions in mental health symptoms in children/youth with maltreatment histories, which is the focus of this study.

METHOD

Participants

The current sample was drawn from consecutive admissions to one RT provider for children and youth aged 6-17 years (n=225, M=12.06 years, SD=2.46, 171 boys). Children/youth who had contact with the Children’s Aid Society (CAS) but were not Crown wards at the time of admission were not part of this analysis, as the intent was to examine CAS that who were intensively involved with child welfare resources. Of the 225 children/youth identified within the time period, 170 children/youth and their families consented to participate in the overall study (for description see St. Pierre et al., 2008). These study participants had in common a history of mental health and behaviour concerns beginning, on average, at age six as well as multiple previous treatments and educational supports being provided prior to their referral to RT.

The total number of children and youth with CAS involvement was 58 (out of the original 170) children/youth (M=11.59 years, SD=2.62, 87 boys). There were 35 children who were Crown wards at the time of admission. Consent to review the Children’s Aid Society files was obtained for 23 (M=11.59 years, SD=1.68, 15 boys) of these 35 children.

Procedure

Ratings were provided on child coping based on two measures. The Brief Child and Family Phone Interview (BCFPI; Cunningham, Pettingill & Boyle, 2004) is a standardized parent/guardian-based telephone interview. Data based on the BCFPI was collected at three different time points: pre-admission, and six-month and two-year post-discharge. The Child and Adolescent Functional Assessment Scale (CAFAS; Hodges, 2000) is a clinician’s rating of functioning of children/youth collected every three months throughout treatment and, by trained telephone interviewers, at the two-year follow-up. Additional data was collected from the casebooks of the Children’s Aid Society for the 23 Crown ward children/youth approximately three years post-discharge using a standardized casebook data retrieval instrument, the Child Welfare Data Retrieval Instrument (CWDRI; Leschied, Chiodo, Whitehead, Hurley, & Marshall, 2003).

Referral Process to RT

All children/youth referred to RT first proceed through their local community single-point-of-access mechanism. This multiple-gating, single-point integrated community intake process utilizes standardized clinical measures within a “least intrusive intervention” model of practice in an attempt to ensure adequate community treatment efforts have been exhausted prior to the child/youth proceeding to RT. This referral process ensures that only those children/youth with extreme levels of need and risk are accepted for RT.

Description of Residential Treatment

The mental health residential treatment program consists of five cottage-like milieu treatment units consisting of three child and two adolescent units. Treatment efforts reflect evidence-based programming elements, which emphasize multimodal clinical assessment, adaptive skill development, family and guardian involvement and co-ordinated discharge planning, which includes a combination of psychological, psychotropic, psychosocial, family-oriented and educational interventions. All participants have an individualized plan of care, formally reviewed monthly by the family/guardian, community case manager, and RT clinicians. Discharge dates are flexible, based on the child’s/youth’s progress and dictated by the needs of each client. The average length of stay for the child/youth in the present study was four months, with outpatient services provided during the immediate pre-admission and post-discharge phases. Post-discharge follow-up could include outreach assistance in the home or classroom as well as ongoing therapeutic contact. Active involvement and support of the parent/guardian is essential. A majority of children and youth in RT return home every weekend, thus over a quarter of their stay while in RT is spent in the community with child and family/guardian goals in place.

RESULTS

Sample. The sample was comprised of N=23 (16 male, 7 female) children/youth who were under the care of the CAS; 95.7 percent of the current sample remained under state-sponsored Crown wardship three years after their initial referral to RT. Age of admission to RT ranged from 9 to 15 years (M=11.59, SD=1.68). The comparison group of non–child welfare involved referrals consisting of N=112 (87 males, 25 females) children/youth with no previous CAS involvement. Age of admission ranged from 6 to 17 years (M=11.59, SD=2.62).

Treatment outcomes

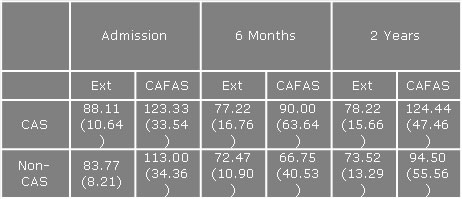

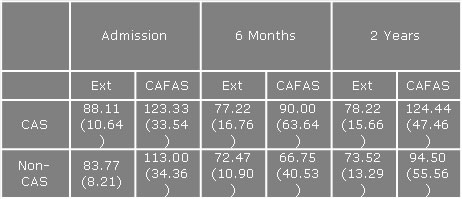

A 2 x 3 split-plot multivariate analysis of variance was utilized to examine differences between CAS and non-CAS referrals over time. The ‘within’ subject factor of ‘time’ was comprised of three levels: admission, six-month and two-year follow-up. A group variable (CAS vs. non-CAS) was utilized as the ‘between’ subject factor. For the purpose of analysis, the ‘externalizing’ component of the BCFPI and CAFAS total scores were isolated as measures of interest. The multivariate effect of the interaction between group and time was not significant, [F (4, 188) = .247, n.s.]; however, the multivariate main effect of time was significant, [F (4, 188) = 8.37, p<.001]. At the univariate level both measures (externalizing, CAFAS total) were significantly predicted by the main effect of time, [F (2, 94) = 12.48, p< .001] and [F (2, 94) = 8.07, p <.001] respectively. Univariate analyses are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Means (and standard deviations) across time points for CAS and non-CAS clients.

DISCUSSION

Differential treatment benefits were compared for seriously emotionally disturbed children/youth with a history of involvement at admission with child welfare, relative to those with no such involvement. Children and youth receiving multidisciplinary residential mental health treatment demonstrated a statistically significant downward trend in reported symptom severity over two years across numerous domains. Behaviour change was most apparent immediately after treatment completion. Findings suggested that both parents and clinicians viewed significant improvement with respect to overall severity of dysfunction and externalizing problems regardless of child welfare status from admission to discharge. These results provide evidence to suggest that a period of four months of intensive inpatient psychiatric milieu therapy combined with community/caregiver supports and full access to a treatment classroom has a significant impact on reducing symptomatology. Overall, some slippage occurred in those gains during the two-year period since treatment occurred, but gains remained below the level reported at admission for parental report.

This data offers parental rating support for the conceptualization of out-of-home mental health treatment as a means to reduce crisis-level symptomatology, reflected in a substantial reduction in behavioural problems and improved functioning. This is consistent with other research (Fernandez del Valle & Casas, 2002) suggesting that outcomes of RT with non–CAS-involved children/youth can be statistically significant and clinically meaningful (Green et al., 2007; Corbillion, Assailly, & Duyme, 1991).

A more fine-grained analysis of the CAFAS sub-scales, however, suggested that CAS children/youth were more likely to develop substance abuse problems at the two-year follow-up, compared to the non-CAS children and youth. This is consistent with other research suggesting that maltreated children and youth have a tendency to cope through the use of illicit drugs and alcohol (Arata, Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Bowers, & O’Brien, 2007; Wall & Kohl, 2007). Researchers have found that all types of maltreatment are associated with substance abuse (Lo & Cheng, 2007) and should be considered a risk factor for substance abuse, particularly during adolescence (Moran, Vuchinich, & Hall, 2004). Given that the strength of the association between maltreatment and substance use varies by the type of maltreatment, youth who have experienced both physical and sexual abuse are at especially high risk for substance abuse (Moran et al., 2004). These findings have implications for the clinical field given that the prevention and treatment of the negative impact of childhood maltreatment should focus on reducing alcohol and drug abuse in adolescence and adulthood (Hamburger, Leeb, & Swahn, 2008).

At this point, identifying the key factors associated with treatment gains within the current sample is not possible. Outcome studies of residential treatment have indicated that family support and the provision of after-care services following discharge are critical to successful reintegration into the community (Hoagwood & Cunningham, 1992). Given that these two factors are the most crucial aspects of treatment sustainability, maintenance of treatment gains may be more problematic for children/youth in care, as there often is no consistent caregiver to work with them during treatment. Previous research has indicated that improved functioning post-treatment can be improved by being discharged into a positive, stable and supportive environment (Quinn & Epstein, 1998). Furthermore, after-care planning can be difficult due to permanency placement problems. For children/youth in “out of home” placements, working closely with foster parents and group home staff is needed to enhance treatment sustainability. Intensive residential treatment can promote a greater understanding of the youth, which can expedite the planning process to permanent care (Milburn et al., 2008).

POLICY IMPLICATIONS SPECIFIC TO CHILDREN IN CHILD WELFARE

There is a significant need to monitor the continuum of care for all children discharged from residential treatment; this is particularly true for children already involved in the child welfare system. Many children and youth within child welfare have some combination of cognitive, adaptive, social and/or behavioural functional impairments (Callaghan, Young, Pace & Vostanis, 2004; Leslie, Gordon, Ganger & Gist, 2002). Mechanisms to ensure that this vulnerable population has timely and adequate access to a co-ordinated mental health service are critical in reducing placement instability among children/youth removed from their homes (Hurlburt et al., 2004; Milburn et al., 2008; Ringeisen, Casanueva, Urato, & Cross, 2008)).

FUTURE DIRECTIONS AND POLICY IMPLICATIONS

Child and youth inpatient treatment for mental health problems is an extremely expensive resource. However, the resources expended reflected in the current study suggest that significant mental health gains can be achieved in the externalizing domains. It can be safely argued that the costs of untreated childhood disorders are equally high if not higher (Scott, Knapp, Henderson, & Maughan, 2001). Further studies examining cost-effective alternative treatment options could possibly alleviate years of child suffering, family dysfunction and parenting stress, and alter pathways of delinquent and antisocial behaviour among many children and youth, particularly those with histories of maltreatment.

REFERENCES

Allen, B. (2008). An analysis of the impact of diverse forms of childhood psychological maltreatment on emotional adjustment in early adulthood. Child Maltreatment, 13(3), 307-312.

Arata, C. M., Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J., Bowers, D., & O’Brien, N. (2007). Differential correlates of multi-type maltreatment among urban youth. Child Abuse and Neglect, 31, 393-415.

Bates, B. C., English, D. J., & Kouidou-Giles, S. (1997). Residential treatment and its alternatives: A review of the literature. Child & Youth Care Forum, 26(1), 7-15.

Callaghan, J., Young, B., Pace, F., & Vostanis, P. (2004). Evaluation of a new mental health service for looked after children. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 9(1), 130-148.

Cloitre, M., Koenen, K. C., Cohen, L. R., & Han, H. (2002). Skills training in affective and interpersonal regulation followed by exposure: A phase-based treatment for PTSD related to childhood abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(5), 1067-1074.

Connor, D. F., Miller, K. P., Cunningham, J. A., & Melloni, R. R. (2002). What does getting better mean? Child improvement measure of outcome in residential treatment. American Journal of Social Orthopsychiatry, 72, 110-117.

Corbillon, M., Assailly, J., & Duyme, M. (1991). The effects of placement and the adult life of formerly placed children. In W. Hellinckx, E. Broekaert, A. Vandenberge, & M. J. Colton (Eds), Innovations in residential care. (pp. 255-265). Leuven, Belgium: Acco Publishers.

Fergusson, D. M., Boden, J. M., & Horwood, L. J. (2008). Exposure to childhood sexual and physical abuse and adjustment in early adulthood. Child Abuse and Neglect, 32, 607-619.

Fernandez del Valle, J., & Casas, F. (2002). Residential child care in the Spanish social protection system. International Journal of Child and Family Welfare, 5, 112-128.

Frensch, K. M., & Cameron, G. (2002). Treatment of choice or a last resort? A review of residential mental health placements for children and youth. Child & Youth Care Forum, 31(5), 307-339.

Green, J., Jacobs, B., Beechman, J., Dunn, G., Kroll, L., Tobias, C., & Briskman, J. (2007). Inpatient treatment in child and adolescent psychiatry – A prospective study of health gain and costs. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48(1), 1259-1267.

Hamburger, M. E., Leeb, R. T., & Swahn, M. H. (2008). Childhood maltreatment and early alcohol use among high-risk adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 69, 291-295.

Hoagwood, K., & Cunningham, M. (1992). Outcomes of children with emotional disturbance in residential treatment for educational purposes. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 1(2), 129-140.

Hodges, K. (2000). Child and Adolescent Functional Assessment Scales, 2nd Revision (CAFAS). Ypsilanti, Michigan: Eastern Michigan University.

Hughes, D. (2004). An attachment-based treatment of maltreated children and young people. Attachment & Human Development, 6 (3), 263-278.

Leslie, L. K., Gordon, J. N., Lambros, K., Premji, K., People, J., & Gist, K. (2005). Addressing the developmental and mental health needs of youth children in foster care. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 26(2), 140-151.

Leschied, A. W., Chiodo, D., Whitehead, P.W., Hurley, D., & Marshall, L. (2003). The empirical basis of risk assessment in child welfare: Assessing the concurrent and predictive accuracy of risk assessment and clinical judgment. Child Welfare, 32, 527-540.

Lo, C. C., & Cheng, T. C. (2007). The impact of childhood maltreatment on young adults’ substance abuse. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 33, 139-146.

Lyons, J. S., Libman-Mintzer, L. N., Kisiel, C. L., & Shallcross, H. (1998). Understanding the mental health needs of children and adolescents in residential treatment. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 29(6), 582-587.

Lyons, J. S., Terry, P., Martinovich, Z., Peterson, J., & Bouska, B. (2001). Outcome trajectories for adolescents in residential treatment: A statewide evaluation. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 10(3), 333-345.

Milburn, N. L., Lynch, M., & Jackson, J. (2008). Early identification of mental health needs for children in care: A therapeutic assessment programme for statutory clients of child protection. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 13, 31-47.

Moran, P. B., Vuchinich, S., & Hall, N. (2004). Associations between types of maltreatment and substance use during adolescence. Child Abuse and Neglect, 28, 565-574.

Newton, R. R., Litrownik, A. J., & Landsverk, J. A. (2000). Children and youth in foster care: Disentangling the relationship between problem behaviours and number of placements. Child Abuse & Neglect, 24(10), 1363-1374.

Quinn, K. P., & Epstein, M. H. (1998). Characteristics of children, youth, and families served by local emergency systems of care. In M. H. Epstein, K. Kutash, & A. Duchnowski (Eds.), Outcomes for children and youth with emotional and behavioral disorders and their families: Programs and evaluation best practices. (pp. 81-114). Austin, TX: PRO-ED. xviii, 738 pp.

Ringeisen, H., Casanueva, C., Urato, M., & Cross, T. (2008). Special health care needs amongchildren in the child welfare system. Pediatrics, 122, 232-241.

Saunders, B.E., Berliner, L., & Hanson, R.F. (Eds.). (2004). Child Physical and Sexual Abuse: Guidelines for Treatment (Revised Report: April 26, 2004). Charleston, SC: National Crime Victims Research and Treatment Center. http://academicdepartments.musc.edu/ncvc/resources_prof/OVC_guidelines04-26-04.pdf

Saywitz, K. J., Mannarino, A. P., Berliner, L., & Cohen, J. A. (2000). Treatment of sexually abused children and adolescents. American Psychologist, 55(9), 1040-1049.

Scott, S., Knapp, M., Henderson, J., & Maughan, B. (2001). Financial cost of social exclusion: Follow up study of antisocial children into adulthood. British Medical Journal, 323(7306), 191.

St. Pierre, J., Leschied, A., Stewart, S. L. & Cullion, C. (2006). Situating the role of residential treatment for high needs, high risk children and youth: Evaluating outcomes and service utilization. RG 160106-003. The Provincial Centre of Excellence for Child and Youth Mental Health at CHEO.

Wall, A. E., & Kohl, P. L. (2007). Substance use in maltreated youth: Findings from the National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being. Child Maltreatment, 12(1), 20-30.

Previous article: Examining the Role of Self Compassion in the Mental Health of A Child Protection Services-involved Youth

|