|

||||

| HOME > Fall 2008 - Volume 52 - Number 4 | ||||

Mental Health of Young People in Care: Comparing Canadian Foster Youth with British and American General Population Youth What the Research Says about the Mental Health of Foster Children It has been estimated that approximately 80 percent to 90 percent of children and youth living in foster care have complex mental health and developmental needs that are related to a diagnosable psychological difficulty (Osborn, 2006; Stein, Evans, Mazumdar, and Rae-Grant, 1996). Commonly reported difficulties include poor interpersonal and emotion-regulating skills, physical and verbal aggression, low self-esteem, and high levels of anxiety (Kufeldt, Simard, and Vachon, 2000; Minnis, Everett, Pelosi, Dunn and Knapp, 2006; Richardson and Lelliott, 2003; Teggart and Menary, 2005). Such difficulties are exacerbated by a greater likelihood of low academic achievement, school suspensions, and problems with the law (Kufeldt et al, 2000; Minnis et al, 2006; Richardson and Lelliott, 2003; Teggart and Menary, 2005). There appears to be a deficiency in the number of young people in foster care who are formally identified as having mental health difficulties (Pasztor, Hollinger, Inkelas, and Halfron, 2006). Many young people in the care of CASs are not formally identified as having difficulties; of those that are, few receive psychological services (Goodman, Ford, Corbin, Meltzer, 2004; Minnis et al, 2006; Pasztor et al, 2006; Teggart and Menary, 2005). Reasons proposed to explain the gap in services include poor coordination between the child welfare and children’s mental health systems to facilitate assessments, and narrow referral criteria for mental health services. However, there is also a scarce number of appropriate tools to aid in the early detection of looked-after children’s mental health difficulties (Callaghan, Young, Pace, and Vostanis, 2004; Kufeldt et al, 2000). The early detection of social, behavioural, and psychological problems among children and youth living in out-of-home care should become a priority to promote young persons’ well-being (Goodman et al, 2004; Minnis et al, 2006). Advantages of screening include helping to expedite referrals for appropriate assessment and intervention services, which, in turn, could help to improve the children’s focus and functioning both academically and socially (Meltzer, 2007; Minnis et al, 2006). One way to promote the early detection of children’s mental health and behavioural difficulties is to use a practical measure such as the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) (Goodman, 1997). The SDQ has been utilized with child welfare populations in several countries (Callaghan et al, 2004; Iversen, Jakobsen, Havik, Hysing, and Stormark, 2007; Minnis et al, 2006; Teggart and Menary, 2005). The evidence of its use among such populations lends to Goodman et als (2004) assertion that the SDQ can be used to improve the “detection and treatment of behavioral, emotional, and concentration problems among looked after children” (p. 30). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) The SDQ is a brief questionnaire that assesses emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity-inattention, peer problems, and prosocial behaviour, of children and youth aged three to 16, over the last six months or school year (Goodman, 2001; Goodman et al, 2004). The SDQ has parent and teacher forms and a self-report version for youth aged 11 to 16. Available in more than 60 languages, it can be used with immigrant children and parents. There are three different forms available: parent report, teacher report, and a self-report for youth aged 11 to 16. Evaluations of the SDQ as a behavioural screening tool have demonstrated its ability to discriminate between community and clinical samples. Goodman et al (2004) showed that multi-informant SDQ rating of looked after children, from the youth, parent, and child welfare worker, resulted in a prediction of a ‘probably’ psychiatric disorder that has a sensitivity of 85percent and a specificity of 80 percent when compared against the independent diagnosis of a clinician. Purpose of the Study The purpose of the current study is to investigate the difficulties youth living in out-of-home care in Ontario, using the SDQ, producing among the first Canadian SDQ data. In the absence of Canadian SDQ general-population norms, the level of mental health among Ontario youth in care was compared to British and American SDQ general-population youth. Based upon previous research with young people in care, it was hypothesized there would be considerably higher prevalence rates of behavioural difficulties in our Ontario sample, compared with the British and American normative samples. The Ontario Looking After Children (OnLAC) Project and the SDQ The present study was conducted within the context of the ongoing Ontario Looking After Children (OnLAC) project, an ongoing study of the implementation and outcomes of Looking After Children: Good Parenting, Good Outcomes (Flynn, Dudding, and Barber, 2006). The Looking After Children approach was originally developed in the UK, and has subsequently been adapted for use in 10 countries. Since 2006, OnLAC was mandated for all 53 Children’s Aid Societies in Ontario by the provincial government and are therefore are required to complete the second Canadian adaptation of the Assessment and Action Record (AAR-C2; Flynn, Ghazal, and Legault, 2006). The AAR-C2 assesses the needs of young people in care and is used to monitor the progress and inform the annually revised plan of care of young people in care. The AAR-C2 is completed in a conversational interview by the child welfare worker with the foster parent and the young person (if he or she is 10 years or older). The AAR-C2 includes many measures that cover the seven Looking After Children developmental domains: health, education, identity, family and social relationships, emotional and behavioural development, and self-care skills. The SDQ was embedded within the AAR-C2 in 2005- 2006, as part of the emotional and behavioural development sections. The foster parent or other caregiver rates the foster child on the 25 SDQ items. Each question is rated on a 3-point scale, in which 0 = Not True, 1 = Somewhat True, and 2 = Certainly True. Each of the five scales—Emotional Symptoms, Conduct Problems, Hyperactivity/Inattention, Peer Problems, and Prosocial Behavior—has a potential minimum score of 0 and a maximum score of 10. A Total Difficulties score is calculated by summing the scores on the four problems scales (i.e., all of the scales except Prosocial Behavior), resulting in a potential minimum score of 0 and a maximum score of 40. When interpreting the SDQ, a young person’s scores on the five scales and the Total Difficulties score are compared to an appropriate normative (community) sample to determine within which of the three categories he or she falls: normal/low behavioural difficulties range, which is below the 80th percentile in a normative sample; borderline/medium difficulties range, between the 80th and 89th percentiles; or abnormal/high difficulties range, between the 90th and 99th percentiles. The SDQ website (www.sdqinfo.com) suggests that the thresholds for the two latter categories can be adjusted upward to avoid false positives or downward to avoid false negatives. Our Participants SDQ data were available for 492 looked-after young people aged 11to 15 (M = 13.18, SD = 1.44), of whom 57 percent were male and 43 percent were female.. Eighty-six percent lived in foster homes, including kinship homes, and 14 percent were living in a group home placement. Study Findings The following results depict the comparison of the OnLAC youth with those general population British youth (aged 11-15, whose SDQ scores were rated by their foster parents or other carers) and American youth (aged 11-14, whose SDQ scores were rated by their foster parents or other carers) for whom normative data was available (see www.sdqinfo.com). The comparisons were based upon the scores obtained by British general population youth whose results placed them within the Borderline and High Difficulties categories on the SDQ subscales and Total Difficulties score. Due to the nature of the sample, the cut-off scores utilized were as close to the borderline and high difficulties bands as possible.

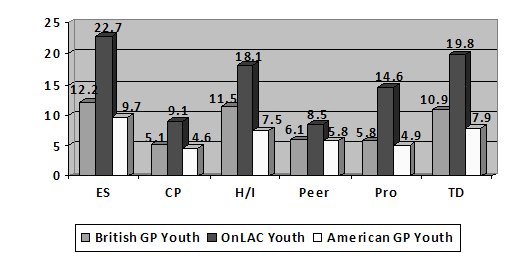

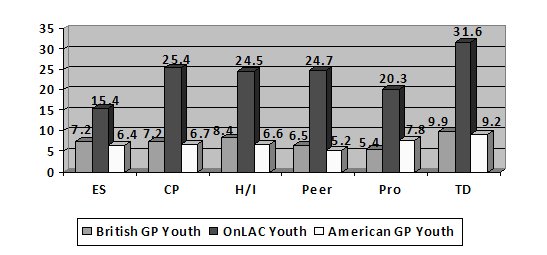

*Because the Prosocial Behaviour subscale measures positive behaviour, lower scores indicate lower levels of prosocial behaviour. Figure 1 shows the results of the comparison between the three populations on subscale scores that are indicative of borderline difficulties. Figure 2 shows the results of the comparison between the three populations on subscale scores indicative of high difficulties. According to the results, there were between one and a half to four-times as many Ontario in-care youths who scored in the at-risk range (i.e., in the high difficulties or borderline difficulties categories) on each SDQ subscale than the British and American general population youth. Moreover, these results demonstrate that over 50 percent of the OnLAC youth in the current sample would be considered high-risk for a likely psychiatric disorder and should be referred for services for further assessment, whereas 21 percent of the British and 17 percent of the American general population youth obtained scores that indicated further assessment would be necessary. Implications of Findings The findings of the present study are consistent with previous research (Minnis et al, 2006) in that the young people in-care exhibited higher levels of problematic behaviour and lower levels of prosocial behaviour than young people of the same age in the British and American general population. These results call attention to how imperative it is that appropriate referrals and services are coordinated in a timely fashion to ensure that looked-after children and youth who are suspected of having identified as having mental health difficulties are referred for further assessment and intervention in a timely fashion. Moreover, the ability of the SDQ to distinguish between looked-after and normative samples suggests it may be as useful in the field of child welfare in Canada as it has in the UK for mental-health screening, referral, and outcome monitoring purposes. One limitation of the present research is the relatively small size of the Ontario in-care sample. However, this problem is only temporary now that Looking After Children is mandated for use in all 53 Children’s Aid Societies in Ontario. Thus, the number of young people in care in the province assessed each year with the AAR-C2 is growing rapidly. By mid-2009, we expect to have annual data on 6000 to 7000 young people in care, which will allow more definitive Ontario SDQ data. The authors note that the early detection of behavioural difficulties and more timely referrals constitute only a useful first step. Current efforts in Ontario and elsewhere to achieve close collaboration between the child welfare and children’s mental health systems are even more crucial. Author’s Note This paper is based upon a presentation made at the conference, Care Matters: Transforming Lives, Improving Outcomes, in July, 2008 at Oxford University. Although the opinions expressed are those of the authors alone, we gratefully acknowledge the collaboration of the Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies and many local Children’s Aid Societies in Ontario in the conduct of the research and the funding provided by the Ontario Ministry of Children and Youth Services. About the Authors Robyn Marquis is a Ph.D. Candidate in Clinical Psychology at the University of Ottawa, Ontario. Dr. Robert Flynn is the Director for the Centre for Research on Educational and Community Services. Marquis and Flynn are both members of the Ontario Looking After Children (OnLAC) Research Team at the Centre for Research, University of Ottawa. References Callaghan, J., Young, B., Pace, F., and Vostanis, P. (2004). Evaluation of a new mental health service for looked after children. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 9, 1359-1045. Flynn, R. J., Ghazal, H., and Legault, L. (2006). Looking After Children: Good Parenting, Good Outcomes. Assessment and Action Records.(Second Canadian adaptation, AAR-C2). Ottawa, ON, and London, UK: Centre for Research on Community Services, University of Ottawa and Her Majesty’s Stationery Office (HMSO). Goodman, R. (1997). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38, 581-586. Goodman, R. (2001). Psychometric properties of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 30, 1337-1345. Goodman, R., Ford, T., Corbin, T, and Meltzer, H. (2004). Using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) multi-informant algorithm to screen looked-after children for psychiatric disorders. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 13[Suppl 2], 26-31. Iversen, A. C., Jakobsen, R., Havik, T., Hysing, M., and Stormark, K. M. (2007). Mental health problems among child welfare clients living at home. Child Care in Practice, 13, 387-399. Kufeldt, K., Simard, M., and Vachon, J. (2000). Looking after children in Canada: Final report. Human Resources Development Canada. Meltzer, H. (2007). Childhood mental disorders in Great Britain: An epidemiological perspective. Child Care in Practice, 13, 313-326. Minnis, H., Everett, K., Pelosi, A. J., Dunn, J., and Knapp, M. (2006). Children in foster care: Mental health service use and costs. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry,15, 63-70. Osborn, A. L. (2006). A national profile and review of services and interventions for children and young people with high support needs in Australian out of home care (Doctoral dissertation, University of Adelaide, 2006). Pasztor, E. M. Hollinger, D. S., Inkelas, M., and Halfon, N. (2006). Health and mental health services for children in foster care: The central role of foster parents. Child Welfare League of America, 33-57. Richardson, J. and Lelliott, P. (2003). Mental health of looked after children. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 9, 249-251. Stein, E., Evans, B., Mazumdar, R., and Rae-Grant, N. (1996). The mental health of children in foster care: A comparison with community and clinical samples. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 41, 385-391. Teggart, T. and Menary, J. (2005). An investigation of the mental health needs of children looked after by Craigvon and Banbridge health and social services trust. Child Care in Practice, 11, 39-49. Next article: The Role of Child and Youth Care Practitioners in Evidence - Based Practice in Group Care: Executive Summary |

||||

| Download PDF version. To change your subscription or obtain print copies contact 416-987-3675 or webadmin@oacas.org |

||||

|