What does anti-oppressive practice (AOP) mean in child welfare?

The theory of anti-oppression helps examine the use and misuse of power at the individual, organizational, and systems levels so that families can receive child welfare services in an equitable way. It also recognizes that families can experience trauma from “us,” the moment we walk up the driveway, or make the call, until the case is closed and beyond. For families, AOP helps level the power platform and empower the family unit and their community to plan for their own outcomes. Shared power goes a long way when working with families and communities that we serve. The position of the responder (direct service or other) becomes that of honoring the family’s story (truth) in the language that reflects who they are, whether we agree with their values or not, to problem solve, refer, preserve family unity, avoid and reconcile traumatic impacts, and plan for permanency in a culturally relevant way. All the while putting biases aside to better understand the situation and check our own social location. Not easy to do.

The whole idea of examining and becoming aware of the power child welfare carries sounds daunting. How do you incorporate these big ideas into your day to day work with children, youth, and families?

Anti-oppression is not a “big” idea so much as it is a grass roots one. It is also not a “new” idea, but one born from voices who’ve called out the inequities of the system. We have a responsibility to respond to that as a sector.

I personally have four main pillars of practice that guide me and go beyond being transparent and following the ministry standards when doing direct service work: the intent to do no harm, to consult, check for systemic barriers, and to be the ally families sometimes need to navigate the system, all stemming from a trauma informed and family driven base of practice. This is something that took me years to build and hundreds of hours consulting with Elders, colleagues, and families.

Why are you so passionate about anti-oppressive practice for child welfare?

Child welfare data has shown and continues to show overrepresentation of Indigenous families which exceeds the number of Indigenous children once held captive in Residential Schools. The statistics also show that there are a disproportionate number in African-Canadian children in care that remain in care for longer durations. That’s pretty troubling. Knowing this should tell us that using AOP is no longer an option for child welfare. We have to meet people where they are at. We can no longer treat all families the same way with a standardized child welfare approach, as all families don’t thrive or survive equally in society.

I am passionate about AOP because I have experienced the success that comes with working with diverse families in an anti-oppressive way, and it makes you want to go there over and over again. When a family feels that you hear them, the stereotypical barriers can come down and solutions flow back and forth more easily. More often than not, families know what they need and where they want to get to, including what they can’t do. The biggest reason to champion AOP is because families want to be treated with fairness and dignity. Leveling the power platform helps do that.

Can you provide an example of how child welfare can oppress a family?

I worked with a mother who had a file opened “on her” when her child was born. After the file was opened, child welfare had very little contact with her over the course of the following year, and did not consider the impact this was having on her. The file simply remained open and was deemed in non- compliance, which is how I got involved. Mom shared with me how she sat in anxiety for a year, waiting for the other shoe to drop. She’d also been involved in her past and was reliving that experience in parallel. She shared that knowing there was a file open on her disrupted her breast feeding and her ability to bond with her child. I worked with her to present her complaint to senior leadership at the Children’s Aid Society. With some coaching, she was able to face them and tell them what the experience was like. This helped reconcile her history with that agency and restored her faith in her own voice. She later reached out for voluntary service and felt safe in doing so.

As you have mentioned, data is showing that there are more Indigenous children and youth in care now than there were in Residential Schools. How have you used AOP to work with Indigenous families?

I worked very closely with an Indigenous father whose children had been apprehended because of addictions issues six years prior to our meeting. The father was alleging that the system wouldn’t allow him to teach his children Indigenous cultural practices and he felt dismissed for having addiction issues. His file review showed there was sufficient evidence that he was trying to take and make opportunities to be a parent during his access visits and I needed to pay attention to this. He was angry because he felt no one was listening. He begrudgingly met me for the first few months, but because of my decision to learn from him, despite his past and despite his view of me and what I represented, we agreed to walk together. What it made me do was take time to get to know them, check my judgements, and take the time to understand addictions. We collaboratively flushed out his frustrations, and we co-developed the service plan with goals that were measurable and achievable for the family.

Can you give me a specific example of a systemic barrier faced by this family?

The template for the family’s court affidavit didn’t use language in an equitable way, it simply prescribed what the family would do. “And the family will abide by Society expectations to…” – this type of language was far too rigid for a family given they had active ideas to contribute to their plan. This was a “power over” type of agreement and I could see the look of defeat and confusion on their faces as they read it, because we hadn’t been working together in this fashion. I asked them, “How can you do this?” What we then wrote in the court affidavit were things like, “The parents will provide medical care for the children with a medical practitioner of their choice,” which enabled them to find somebody in their own community at no additional cost or burden to them while still fulfilling their responsibility. Systemic demands can put families in an impossible situation, and a little consultation to get their viewpoint can make all the difference.

How did things work out for this family?

The kids returned home a year after I first met this family, and they flourished the minute they got home. I saw this father’s son rush out my vehicle and full on jump on his dad in a full body embrace. It was the most beautiful thing I had ever seen.

This family also got their chance to meet with senior leaders to talk about their experience and to reconcile their past. They told me they’d finally felt the power of their own voice. That took a lot of coaching on my part, but I would do it again in a heart beat.

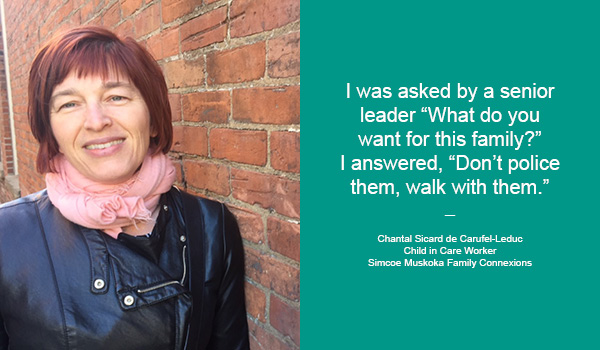

During the meeting, I was asked by a senior leader “What do you want for this family, Chantal?” I simply answered, “Don’t police them, walk with them.” There were a lot of handshakes that day and the family has stayed united since. The kids are now adults and working.

What kind of challenges do you face practicing A/O?

There are many worthy challenges. Effective anti-oppressive practice requires acknowledging how you can potentially contribute to oppression by getting to know your own biases and that in itself is tough. Learning to see systemic barriers takes a lot of practice although once you see them, it’s almost impossible to “unsee” and that can be a challenge too. Helping colleagues see systemic barriers is likely the toughest challenge of all, but we can learn a lot from one another when we have the moral courage to out those barriers. Yours can be the lone voice when challenging the status quo. It means that sometimes you risk going against the predominant view, but a calculated risk is potentially worth a family’s voice permeating through the status quo. That’s a win for families and on its own can sometimes restore their faith that the system can help.

How important is self-care when you do this work?

Workers in the child welfare sector feel the many systemic pressures to comply, perform, and achieve equitable outcomes for families. You cannot do this job, (no matter at what tier) without self-care, and I am not talking about Costco cards and massages. Building relationships with families while working the system requires an awareness of our mental health much like training in the gym. It’s good to know the risks of vicarious trauma, it’s good to know your own limits and when to pull back, but it’s imperative that agencies particularly champion and support the mental health and overall wellness of those who do this work.

If you could wave a magic wand, what would you wish for AOP and child welfare?

I used to think that senior leaders needed people like “us” to watch for when oppression occurs, but what I’ve learned is that we need senior leaders, now more than ever, to model, promote and be the change so that others can follow in an anti-oppressive way. This is especially important given the increase in Ministry expectations and our limited financial resources. Senior leaders can be excellent champions in changing policies and challenging oppressive practices and culture within an organization and moving us from a standard and policy centered practice to a family and community- based service delivery model. Ultimately though, the change has to happen with all of us.

You must be logged in to post a comment.